Last month, despite the chaos of buying a house and moving to it for the first time in my life, I managed to read Education and Society in Salazar’s Portugal1, by sociologist Maria Filomena Mónica. Salazar’s regime began in 1933 and ended in 1974 (even outlasting his death in 1970), but this book focuses particularly on education in Portugal in the 1930-1940 period. It is a carefully curated collection of chilling facts, capable of disabusing anyone of the notion that they have understood the evil of the Estado Novo regime, or the society which preceded it, to its fullest extent.

Growing up with liberal parents and having been educated in a liberal country, it’s almost impossible not to develop a certain infantile, simplified idea of historical progress, detached from the real, bloody, consequential struggle between groups of opposing interests. I admit I had never paid too much attention to how primary education became free and universal in Portugal. These were factoids I memorized for a History test (or several): that the teaching of reading, writing and basic arithmetic was relegated to religious orders, namely to the Jesuits, until 1759, when the Marquis of Pombal secularized education by creating the aulas régias (“regal classes”?); that several reforms during the Constitutional Monarchy (1820-1910) and the First Republic (1910-1926) periods aimed to make this level of education mandatory; and, lastly, that primary education only became de facto mandatory (and even then, not always) during the Estado Novo (“New State”) dictatorship (1933-1974).

I suppose I thought that at some point it had occurred to people in power to be decent, and give people their due rights — this is mostly how we are taught to think about historical progress. As I grow older and begin to read more broadly, I realize that historical progress is only ever the result of armed struggle on the part of the oppressed, or of ulterior motives on the part of the oppressor. The Marquis of Pombal secularized education because he wished to disempower the Church, to curb its power over men’s minds; the constitutional monarchy government attempted to broaden the scope of primary education so as to facilitate the acceptance of constitutional monarchy, as opposed to the old kings’ absolutism, and to prepare young boys and girls for a factory regimen; the First Republic broadened the scope of primary education yet more because it wished to teach the people the virtues of republicanism, and the evils of the Church; and, finally, the Estado Novo government universalized public education to indoctrinate the people with its own values, which I will soon discuss.

In 1930, 62% of 7 million Portuguese were illiterate (and 80% lived in the countryside). In spite of this, the powers that were did not come easily to the conclusion that alphabetization was a historical and moral necessity. There was, on the contrary, much discussion of the topic, and many stringent voices arguing against it: the rural Portuguese bourgeoisie argued that school did nothing more than steal labor force from the fields; Estado Novo deputy Querubim Guimarães asked parliament, with great rhetorical flair, whether Vasco da Gama’s men-at-arms knew how to read or write; deputy Pacheco de Amorim called child labor “a fine school of responsibility”; 4 years prior, a decree-law had stated that “there was no advantage in giving children substantial amounts of knowledge, since the mind, like other organs, possessed a mechanism which expelled what was fed to it in excess”. One particularly heinous woman, named Virgínia de Castro e Almeida, went yet further, decrying the evil applications to which the people were wont to give their literacy, and boldly stating: “Blessed are those that forget their letters and return to the spade. The most beautiful, strongest and healthiest part of the Portuguese soul resides in those 75% of illiterate folk.” (She was speaking in 1927). There also seemed to be a bizarre notion that the Portuguese people, as a people, were disinterested in education, since up until then the (largely rural) population had largely refused to send their children to school. The kindest assumption here is that it never occurred to these brilliant theorists that no social mobility came from literacy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Portugal, and that school did indeed “steal labor force from the fields”, which meant stealing food from the plate. A less kind assumption would be that the people who propagated this notion knew they were lying; that they put Salazar in power (or allowed him to step into it) because, like him, they had “a firm pulse and their eyes open”, and “knew very well what they wanted and where they were headed”.

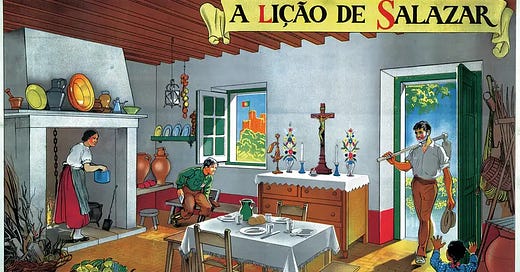

There were, indeed, two great disadvantages to universal literacy: it cut down on child labor, and it gave people social hope, and a marginally better understanding of the world. But then again, there was one great argument in its favor: education was the surest way of social control, especially for a dictatorship which, despite the brutal horrors it committed, prided itself on “being so strong that it need not be violent.” The people ought to learn how to read and write and how to understand basic mathematics so as to do their lowly jobs competently, and so that they may efficiently internalize Catholic dogma and the unquestionability of the Estado Novo regime.

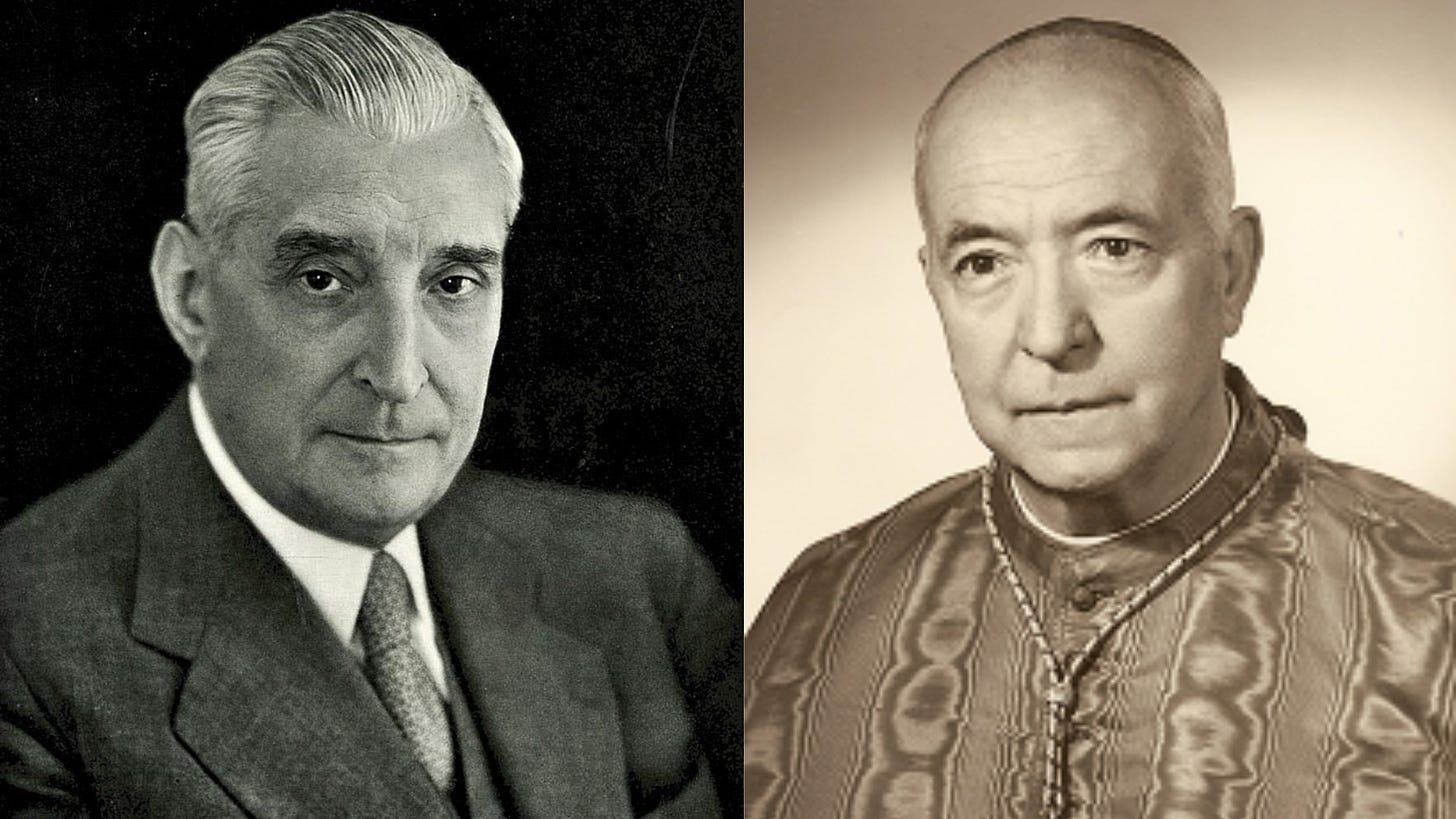

If Salazar’s long, shrewdly hypocritical face was the symbol of (and the driving force behind) the Portuguese Government, then the round, amicable features of Cardinal Cerejeira, Patriarch of Lisbon, were the herald of the Portuguese Catholic Church. Just as these two men were close friends, so too did Church and State promiscuously legitimize each other’s monstrosities. Cardinal Cerejeira thought of the Catholic religion as one which ordered its subjects to “comply with, respect and obey” their temporal masters, and saw Salazar as a leader “chosen by the Lord”, to whom obedience was owed as much as to God. In return, Salazar preached in an infamous 1936 speech with his frail nasally tone that still echoes in many living minds:

“We do not question God and virtue; we do not question the Fatherland and its History; we do not question authority and its prestige; we do not question the family and its morality; we do not question the glory of labor and its duty.”

Indeed, primary education did little to educate the people (estimations of functional literacy were low even decades on), but it succeeded in reframing the crimes of Portuguese colonialism as heroic, to “feed the great certainties in the collective soul”, and you can still find people alive today educated under Salazar whose every class began with a recitation of the Catechism. No wonder, then, that in his usual sinister style Salazar chose to call schools “the sacred workshops of the soul”.

I don’t wish to end this small essay on a depressing note, so I’ll hint at the falsity of another lie often told about the Estado Novo dictatorship: that the Portuguese people, known for its “meek customs”, accepted their oppression, did little to stop it, and patiently awaited the liberation that came by the hand of the Armed Forces Movement (a movement within the Portuguese army) in 1974. Although this is — honest to Christ — what they teach us in school, it could not be further from the truth. The Resistance in Portugal, by Miguel Dias Coelho, tells a long, extraordinary story of legal and illegal, peaceful and violent, vain and successful resistance to the atrocities of Estado Novo. The tools of Salazar’s workshop were blunt, and inarticulate in comparison to the urgency of an empty stomach and an outraged conscience.

Original title: Educação e Sociedade no Portugal de Salazar